Great Figures to Communicate Your Science

Great figures are invaluable in communicating science effectivity to diverse audiences. Good figures reinforce and strengthen the narrative presented in the text. This guidance summarises some of the approaches that we generally prefer in TESS lab but is not prescriptive as styles can vary in different disciplinary areas and publications.

Tips for Figures

Where possible and appropriate, try to show the data rather than only summary metrics (e.g., a central tendency such as mean or median) in data visualisations. Plots that show all the data allow readers to intuitively grasp the sample size, the extent of variability in each sample and the distribution of this variation.

Take care to ensure that your figures are completely legible at a 100% reproduction size (avoiding tiny text!).

It is important to use appropriate colour palette to maximise the accessability and interpetability of our figures. For more information, see viridis vignette and also this blog introducing the turbo palette. An estimated ca. 5% of the global population has some form of colour blindness.

To reduce distortion in global maps, we should use a suitable projection to avoid perpetuating biased and misleading representations of our planet. The ‘Winkel Tripel’ projection is best (required by National Geographic), though the ‘Mollweide’ and ‘Robinson’ projections are also both much better than the (highly distorted) ‘Mercator’ projection that is usually the default in most geospatial software (more info). In R this can usually be achieved with one extra line of code.

Figure Captions

Figure captions are often vital to ensuring that readers understand and correctly interpret a figure. Any graph or image in a report is incomplete without a proper caption. Figure captions should be standalone, i.e., descriptive enough to be understood without having to refer to the main text. Effective captions typically include the following elements:

- Figure Number. Figures are normally identified by the capitalized word Figure and a number followed by a period and then the rest of the caption. Figures should be numbered using the order in which they appear in a text (i.e., “Figure 1.”, “Figure 2.”…). Occasionally figures can also be identified by double numbering in which the first number identifies the chapter and the second number identifies the figure (e.g., “Figure 4.5.” might refer to the 5th Figure in Chapter 4).

- A declarative title that summarises the main finding presented in the figure in the first sentence;

- Often a brief description of the key methods necessary to understand the figure without having to refer to the main text and sometimes statistical information, for example, sample sizes, statistical significance, specifications of what statistics are shown (esp. average, range, for box plots), etc.

We like declarative titles because:

- They help readers quickly and correctly understand the main take-home message, improving the accessibility of the text and reducing the risk of misinterpretations.

- Writing in this style can help focus the author(s) at the development stage to create figures that communicate the main point most effectively.

- Ensuring that the main message(s) are explicit can help avoid (unintentional) publication of incompletely interpreted data.

Declarative titles are sometimes controversial as traditionally figure captions were just objective statements of the variables being presented (e.g., “Scatterplot showing the relationship between X and Y”), leaving the reader to draw their own conclusions from each figure and some people felt that declarative titles were too subjective. However, the reality is that we already express an (acceptable) level of subjectivity in the rest of every output, from the title onwards, and we think in modern science communication that would be counterproductive to state conclusions overtly in the title and main text but hide them in the figures.

Example Figure Captions

Example Figure 1. Point clouds derived from UAV surveys provided structural reconstructions of plants across globally distributed non-forested ecosystems. Our sampling across four continents (A) encompassed five bioclimatic zones where low stature vegetation is often dominant, representing most of the non-forest biomes described by Whitaker (1975) (B). Reconstructed point clouds with grid of black points representing the modelled terrain correspond strongly with photographs of harvest plots (C).

(from Cunliffe et al. 2022).

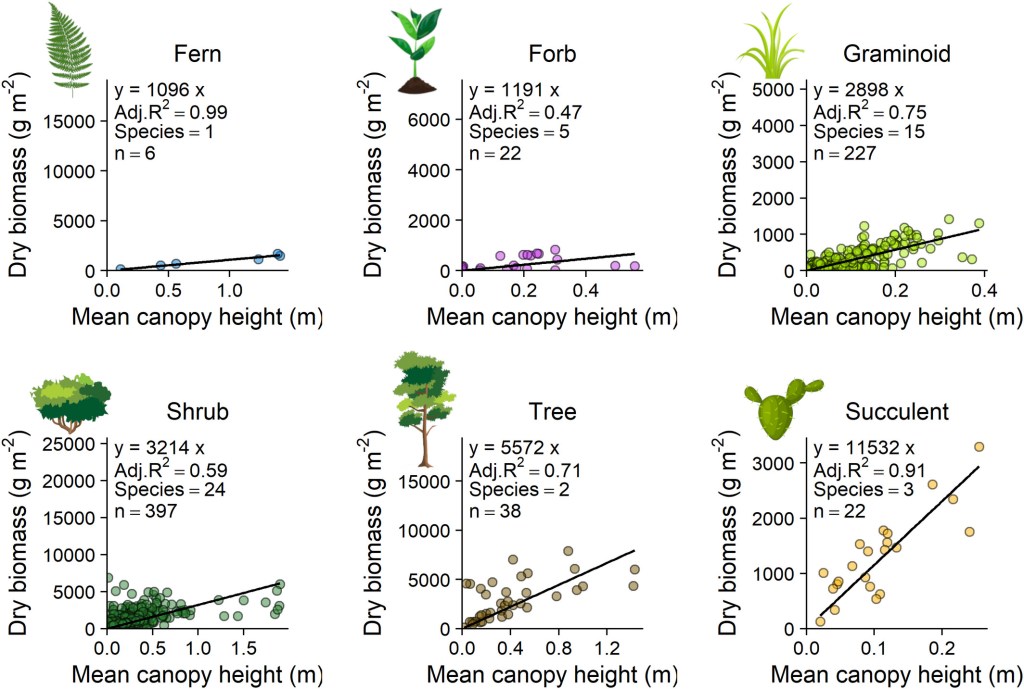

Example Figure 2. Photogrammetrically derived canopy height was a strong predictor of biomass within most plant functional types. A constant X:Y ratio was used for all plots, enabling visual comparisons of model slopes even though axis ranges vary. Model slopes were generally similar within but differed between, plant functional types. ‘Species’ indicates the number of species pooled for each plant functional type and black lines are linear models with intercepts constrained through the origin. Full model results are included in Table 1.

(from Cunliffe et al. 2022).

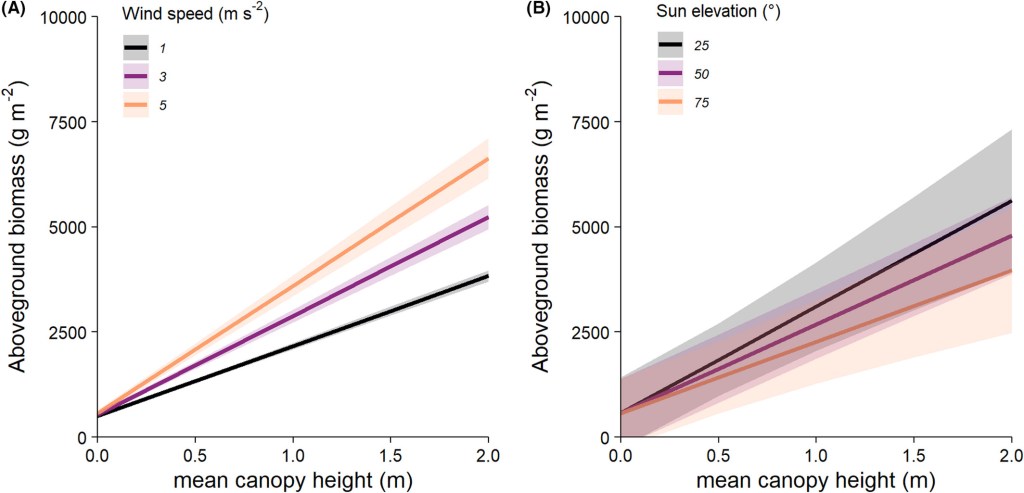

Example Figure 3. Reconstructed plant height and thus height–biomass relationships were systematically influenced by near-ground wind speed but were insensitive to sun elevation. Mean predicted aboveground biomass variation over the range of observed mean canopy height, estimated for a range of three wind speeds and sun elevations. Wind speed had a statistically clear and positive effect on the relationship between height and biomass (A) (Figs. S2A and S3, Table S3) but sun elevation had no significant effect on the relationship between height and biomass (B) (Figs. S2B and S5, Table S5). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals on the model predictions.

(from Cunliffe et al. 2022).

Example Figure 4. Aboveground biomass was strongly predicted by canopy height but less strongly by NDVI. For each harvest plot, the mean canopy height was measured with point-intercept (a) and structure-from-motion photogrammetry (b), and mean NDVI was extracted from the 0.119 m grain raster (c). Linear models with constrained intercepts were fitted using least mean squares optimisation, with constrained intercepts for the canopy height models. The linear model fit is a simplification of the likely saturating relationships that we would expect to find across the full variation of NDVI and biomass values.

(From Cunliffe et al. 2020)

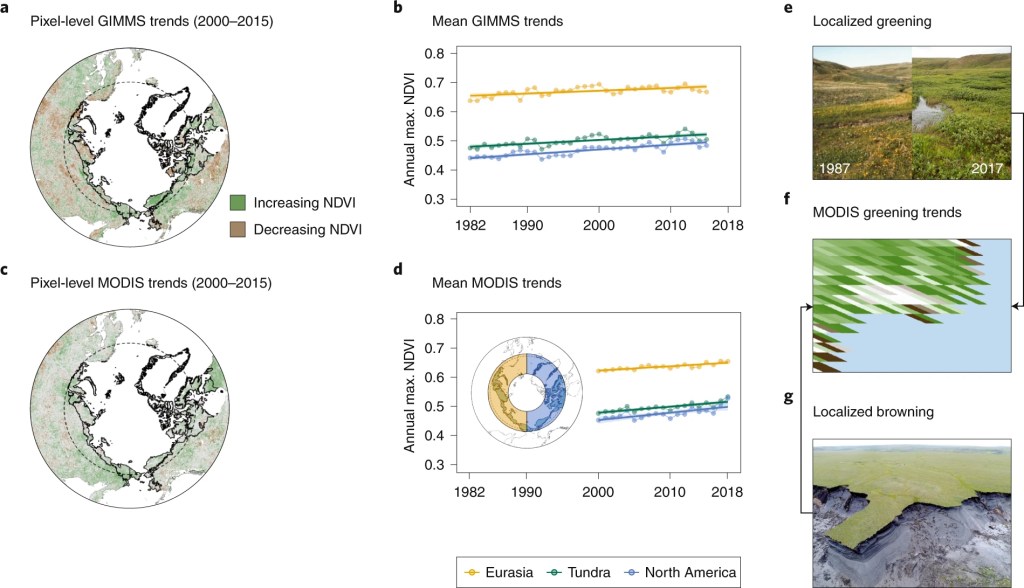

Example Figure 5. Apparent Arctic greening, which varies across space and time and among satellite datasets, is driven both by actual in-situ change and, in part, by challenges of satellite data interpretation and integration. a–d, Trends in maximum NDVI vary spatiotemporally, and the magnitude of changes depends on what satellite imagery is analysed (a and c, data subsetted to temporally overlapping years; b and d, data from the Global Inventory Modeling and Mapping Studies dataset from AVHRR (GIMMS3gv1) 1982 to 2015, and MODIS MOD13A1v6 2000 to 2018). e–g, Regional trends may summarize localized greening, for example shrub encroachment (e) and browning such as permafrost thaw (g) occurring at the pixel scale on Qikiqtaruk–Herschel Island in the Canadian Arctic (f). NDVI trends (a and c) were calculated using robust regression (Theil–Sen estimator) in the Google Earth Engine130. Dashed line indicates the Arctic Circle, and the black outlined polygon (a and c) and green ‘tundra’ line (b and d) indicate the Arctic tundra region from the Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map (www.geobotany.uaf.edu/cavm/). The inset map in d indicates the regions for the mean trends for yellow ‘Eurasia’ and blue ‘North America’ polygons.

(From Myers-Smith et al. 2020)

Example Figure 6. (a–d) Temperatures are warming, (e) frost frequency is decreasing, (f) the snow melt data is getting earlier, (g) sea ice concentrations are lower, and (h) soil temperatures are warming on Qikiqtaruk. Changes in climate and environmental data from Qikiqtaruk including air temperatures (a–d; Environment Canada data), frost day frequency (e; the number of days that the mean temperature is below zero, CRU TS3.21 data), snow melt date (f; phenology monitoring), sea ice concentration (g; minimum proportion of ice to open water Canadian Sea Ice Service data for the CIS WA Beaufort Sea: Mackenzie region), and soil temperature at 12, 15, and 16 m depths from two different boreholes (h; soil temperature monitoring data). Three records with outlier values were not included in the models in panel h for the years 2007 and 2012. Air temperature plots show mean values for the months indicated. Trends lines are Bayesian model fits with error of 95% credible intervals. Full model outputs can be found in Appendix S1: Table S2.

(From Myers-Smith et al., 2019)

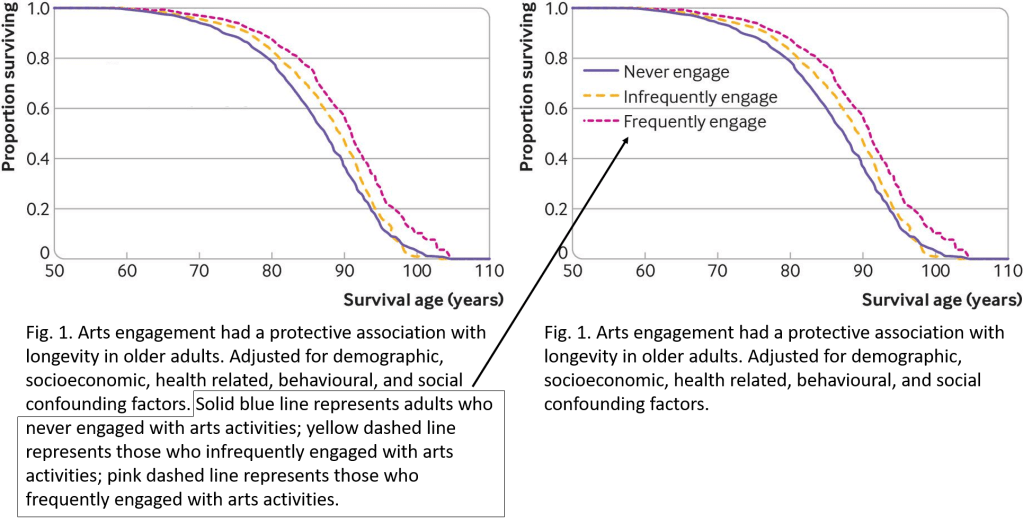

Check your captions to ensure that elements are in the right place, especailly for information that would be better presented within the figure itself (example below).

For most scientific outputs, we should position captions under figures (instead of titles within figures). While captions are occasionally placed becide or even above figures, the decision to place captions in uncommon locations should normally only made by the production editor, not by the writer(s).

Table Titles

Table titles should go above the table. Table titles do not contain descriptions but they may include additional necessary information.

Links for further resources

- https://dynamicecology.wordpress.com/2024/03/04/convey-the-key-message-of-your-figure-in-the-first-sentence-of-the-legend/

- https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/viridis/vignettes/intro-to-viridis.html

- https://erinwrightwriting.com/how-to-write-figure-captions/

- https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/figures-and-charts/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-019-0688-1

- https://www.internationalscienceediting.com/how-to-write-a-figure-caption/

- https://www.scu.edu/media/offices/provost/writing-center/resources/Tips-Figure-Captions.pdf

- Kroodsma DE. A quick fix for figure legends and table headings. The Auk. 2000 Oct 1;117(4):1081-3.